Love and Care is more important than DCRs or Heroin Assisted Treatment

18/10/2023

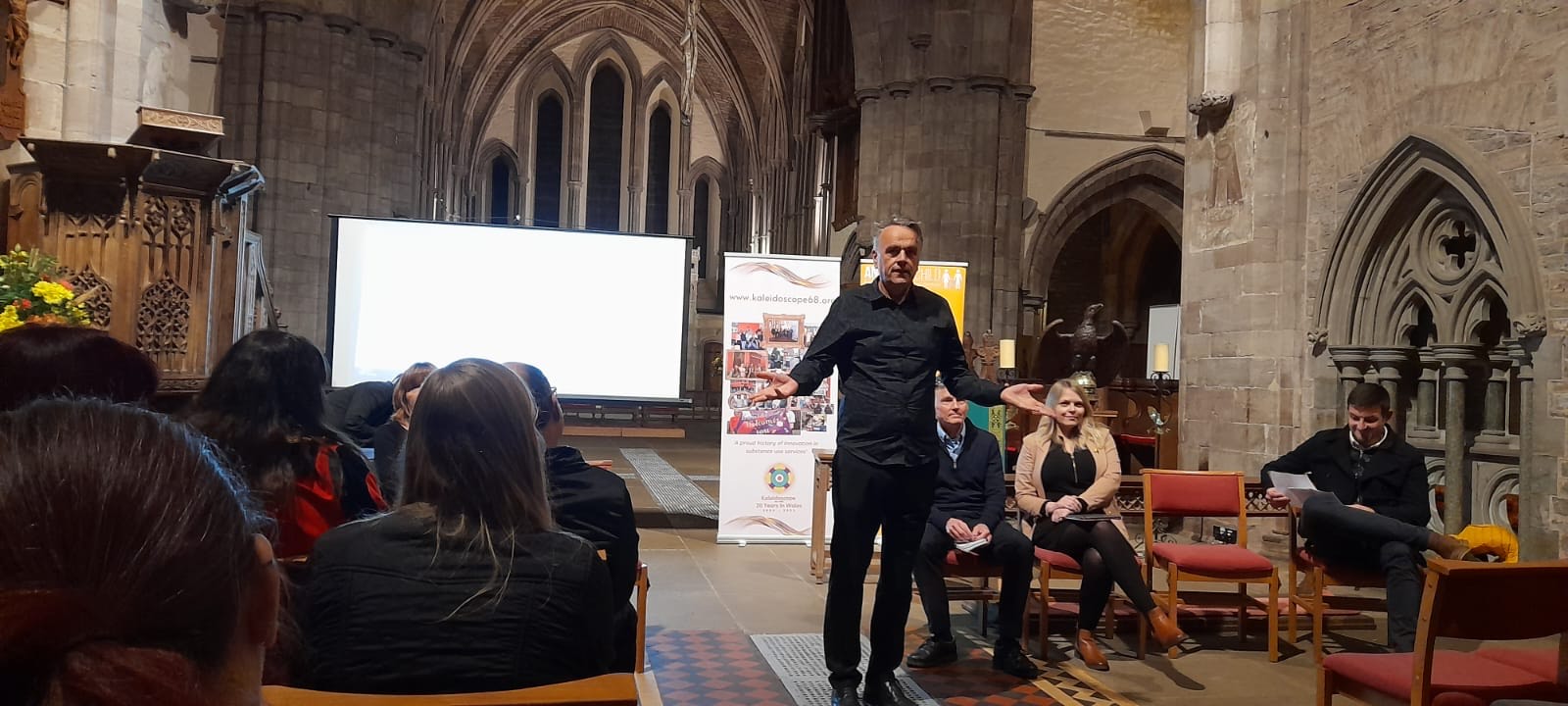

On Monday 16th October we were delighted to be part of Brecon: Take Drugs Seriously. One of the most important issues to discuss at the event was the recent announcement in Scotland of their intent to run a Drug Consumption Room that would not be opposed by the UK Government. Like many who work in the field of providing drug services I am truly excited that in Scotland they have agreed to allow Drug Consumption Rooms (DCRs), but in similar measure it concerns me.

In my 25 years at Kaleidoscope I have learnt that the best service we can offer is one that creates an environment of hospitality, with a staff team who enjoy helping the people who come into our service bases for support. We want to provide the best evidence-based treatment options, for example rapid prescribing or Buvidal. However, we know that good medical service or case working without a welcoming space in which those services are delivered means that your attempts to help are far more likely to fail.

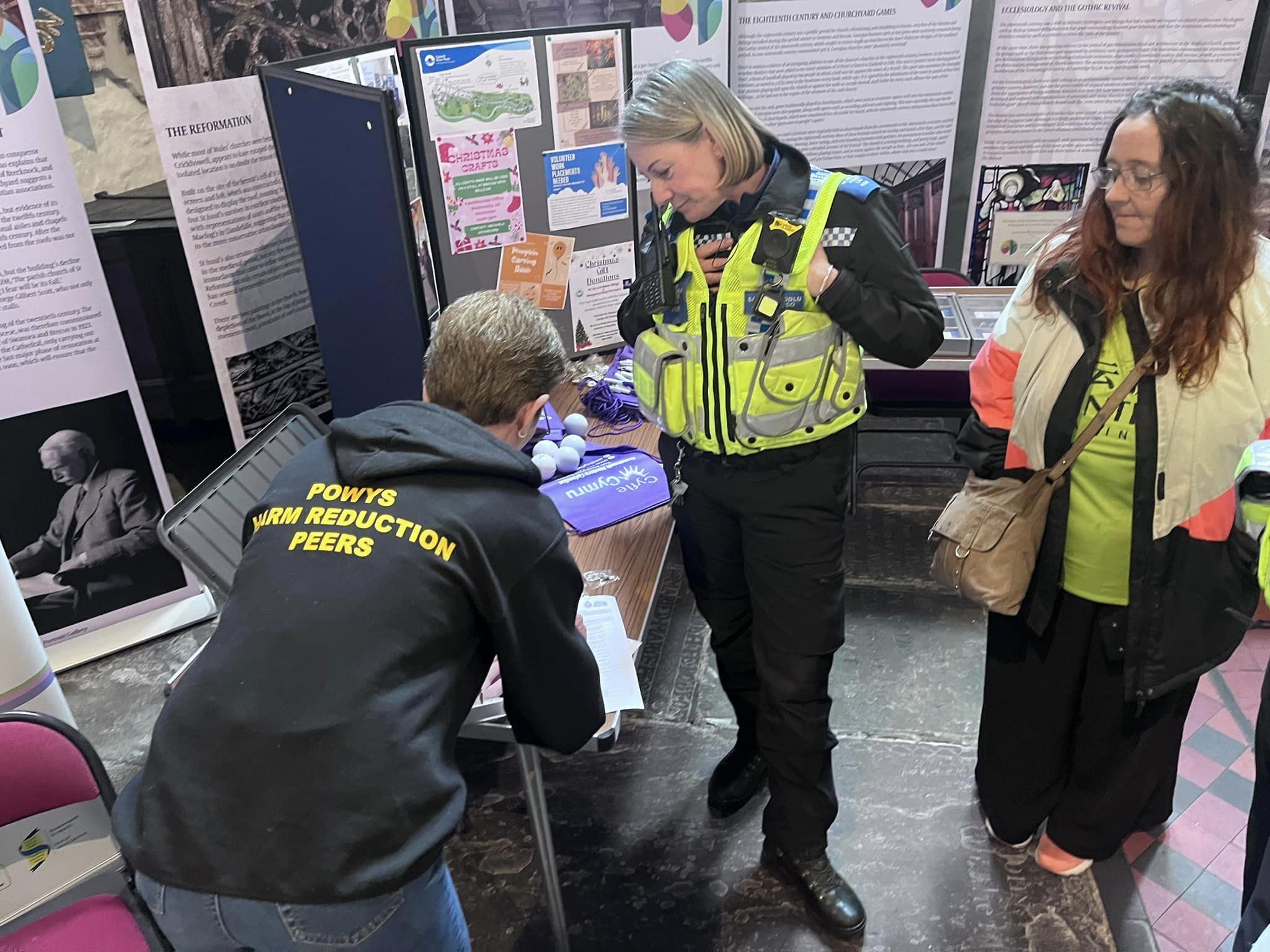

In recent years we have seen the power in peers supporting peers. In Wales this is showcased in the roll out of the nationwide peer to peer Naloxone programme. We want to involve the people who use our services in designing and helping to plan future provision. One of their key asks is creating a safe place to inject their drugs.

There are people who argue against Enhanced Harm Reduction facilities because they believe such a facility will encourage drug use. The problem with such an analysis is that very few homeless injecting drug users choose this life. The reality is that the wrap around services they would need are simply not there. If a homeless person with mental health issues is using drugs because they perceive it as the only effective solution to their immediate problems, there are no mental health services in place to support them whilst they’re still an active user. In the Brecon event we were told that there are two dual-diagnosis workers covering Powys, the largest County in Wales. This can only make a meaningful difference to a small portion of the population who need this kind of help.

If mental health support was increased so that those who need it were able to get it, there would still be the obstacle of accommodation. The offer of a home is extremely rare and most of the people we work with would be placed either in B&B or a hostel, which would be far from ideal and for many who have dogs it would be an impossibility for them to take this up. Even if there was accommodation that worked, is there any employment opportunity for them given their health issues, often both mental and physical in nature?

No one likes to look at costs but sadly there is a limit that any Government will spend on providing services to vulnerable people. The ideal would be providing the wrap around services that everyone needs, but our failure to be able to do this means that sadly there will continue to be those who use drugs to get a sense of wellbeing.

I accept that there are limited budgets and therefore we need to be careful in the way that we spend public money. If a facility that enables people to take their own drugs costs a huge amount of money, which therefore limits other vital services to this group of people, it surely cannot be justified.

Annemarie Ward, CEO of FavorUK points out that, in Scotland the proposed DCR will cost over 2 million pounds, which is spent on a very limited amount of service users. Could that money be better spent on other vital services, such as residential detox and rehabilitation services? Annemarie notes that despite there being 18,062 problematic drug and alcohol users in Glasgow there are only 23 publicly funded rehabilitation beds.

The other startling reality of Scotland is poor engagement in treatment services. Sadly, the offering is very medicalised and the NHS, as the main provider, has a poor record of letting service users co-design. The existing cost of the Scottish System is the highest in the UK but with the worst outcomes in Europe. Yes, they have heroin assisted treatment, and now they will have the first drug consumption rooms, but unless they quickly find ways of providing services that people want to attend and then ensure the whole treatment system is properly funded, these very valid enhanced harm reduction techniques may be doomed to have only marginal impact on the broader picture.

Critics of DCRs argue that such moves will not actually have a huge impact on drug deaths. It may be almost impossible to assess how successful such services are in saving lives. This is because of factors such as heroin purity, the social economic situation and access to other support services. The evidence does show that DCRs are relatively safe, certainly overdoses have been reversed in them, but more importantly drug deaths from overdose are not the key reason for needing for such facilities.

One of Kaleidoscope’s motivations is to reduce the stigma people who take drugs suffer from. Discarded needles and open injecting, which naturally frightens the wider public, is the most significant issue that stigmatises people. The people injecting in public places are often homeless and have no other place to go. Therefore, providing a place away from the public glare is important. It takes away the public fear of drug use and the risk of a child picking up a needle is much reduced.

For a service user the importance of being able to inject as safely as possible is vital, making it possible for them to reduce drug wounds that cause such a risk for them in terms of infection. As an agency we would be able to work with partners, such as WEDINOS, in testing the drugs that they are taking, so we can alert users of particularly dangerous batch of heroin. The significant reduction of the opium farming in Afghanistan could seriously change what drugs people will take and there is reasonable fear that illegal pharmaceutical drugs could be a lot more dangerous than the plant-based drugs they may replace.

One reason why people that take drugs do not engage with services is because they do not trust them. Drug consumption spaces have proven to better engage people because they are often anonymous, and they provide the services the person wants. They only need to give very minimal personal information and confirmation that the drugs used are theirs. There is a mistrust of the opiate prescription process because it can make some service users feel that they are being coerced or controlled. The lack of faith in any help is very ingrained for these people and it is hoped that by reaching out to them with such service, they may be willing to give other treatment options a chance.

Drug Consumption Rooms must be co-produced with people who use drugs. A top-down bureaucratic approach could often harm people because it is based on a stigmatised view of the issues they face. The lessons from Glasgow by the work of Peter Krykant were two-fold. Firstly, as an activist he was fed up with the lack of progress in providing drug consumption rooms and by simply doing it he has thrown open the doors for providing such services. Secondly, he does not hide from his own experience and as a peer he engages people as I never would be able to. The facility he had, a disused ambulance, was far from ideal but it worked because he is both engaging, loving and caring of the people who need such help. The key to the success of such services going forward must be to enable activists, people with lived or living experience to provide such services. A bold move in this direction will make DCRs affordable, and more importantly will engage people in a way that many of us have failed to do so far.

Martin Blakebrough

CEO, Kaleidoscope